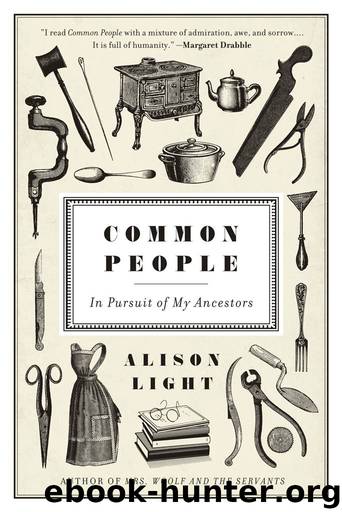

Common People: In Pursuit of My Ancestors by Alison Light

Author:Alison Light [Light, Alison]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2015-09-16T21:00:00+00:00

Sarah was admitted to Netherne on 9 June 1911, her first and only admission. Public asylums like Netherne were Poor Law institutions and it was necessary to be registered by the local relieving officer as a pauper. The Epsom Union workhouse was the first stop for many of those who arrived at Netherne, local people like Kate Reigate, with nothing apart from ‘sad case’ by her name; John Russell of Chessington, a labourer in his mid-forties, styled ‘village idiot’; and John Peters, categorized as ‘immoral’ and ‘admitted at his own request’. All were removed from the workhouse wards by an order from the magistrate to Netherne not long after its opening. Carshalton, where the Smiths lived, fell into the Epsom Union but Sarah was not in the workhouse. She was still at home when her husband filled in the census form in March 1911, two months before she was committed. There was no sign of her in the Brookwood Asylum records either, so I knew she had not been transferred. Under the column in Netherne’s register which commented on her condition—whether ‘Recovered, Relieved, Not Improved, Died’—it merely read ‘Died’. The register of deaths confirmed the information on her death certificate: she died on 18 June from ‘exhaustion’ after sixteen days of mania. Seven days were unaccounted for but were most likely spent at home until the family called in a doctor. I would learn nothing more except that she was ‘buried by friends’, a phrase that included family, though not at Netherne. There were no other medical notes for Sarah. The patient ‘case books’, or case files, for Netherne’s early period have not survived (and only a small sample, about 10 per cent of case files from the Epsom cluster asylums, were kept).

There were more questions than answers. ‘Mania’ is deemed a ‘mood disorder’, generally characterized as a state of wild, feverish elation, a hyperactive state of restlessness and often irritability, which leads to sleeplessness. But in the nineteenth century ‘mania’ was an umbrella term. More than 80 per cent of admissions were for mania; today it would be less than 5 per cent. Under its rubric sheltered many conditions which would now be diagnosed differently, including many organic illnesses. In the days before antibiotics, patients became delirious from high fever, while other acute medical illnesses—brain damage, cancer—might exhibit ‘psychiatric’ symptoms; some patients might be suicidal, others senile or epileptic; still others would now be labelled ‘schizophrenic’ or ‘psychotic’. I could see from the register that patients at Netherne also died of exhaustion from ‘melancholia’, but the idea of linking alternating and recurring ‘phases’ of excitement and stupor was not to take hold in Britain until after the First World War when an English translation of Emil Kraepelin’s theory of ‘manic depression’ was more widely available. Sarah was fifty-three. She may well have been in an asylum earlier in her life elsewhere in the country or have periodically suffered from depression without it being seen as anything other than the utter weariness of a working woman.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26560)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23021)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16819)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13235)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7070)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5455)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5056)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4905)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4768)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4761)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4420)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4319)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4226)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4143)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4053)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3996)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3918)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3605)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3440)